Our forests protect us – Judith Wright on East Gippsland’s forests.

I know, on the last day of the year you are supposed to get a year in review. Not from me you won’t; I am sick of hearing and reading 2017 reviews and don’t think in these neat 12 month segments in any case.

I know, on the last day of the year you are supposed to get a year in review. Not from me you won’t; I am sick of hearing and reading 2017 reviews and don’t think in these neat 12 month segments in any case.

I prefer to think ahead as the urgency of our task grows every year as once more governments, corporations and most households fail to take on the climate and biodiversity crises which await us.

That’s what I’m going to be thinking and writing about this year.

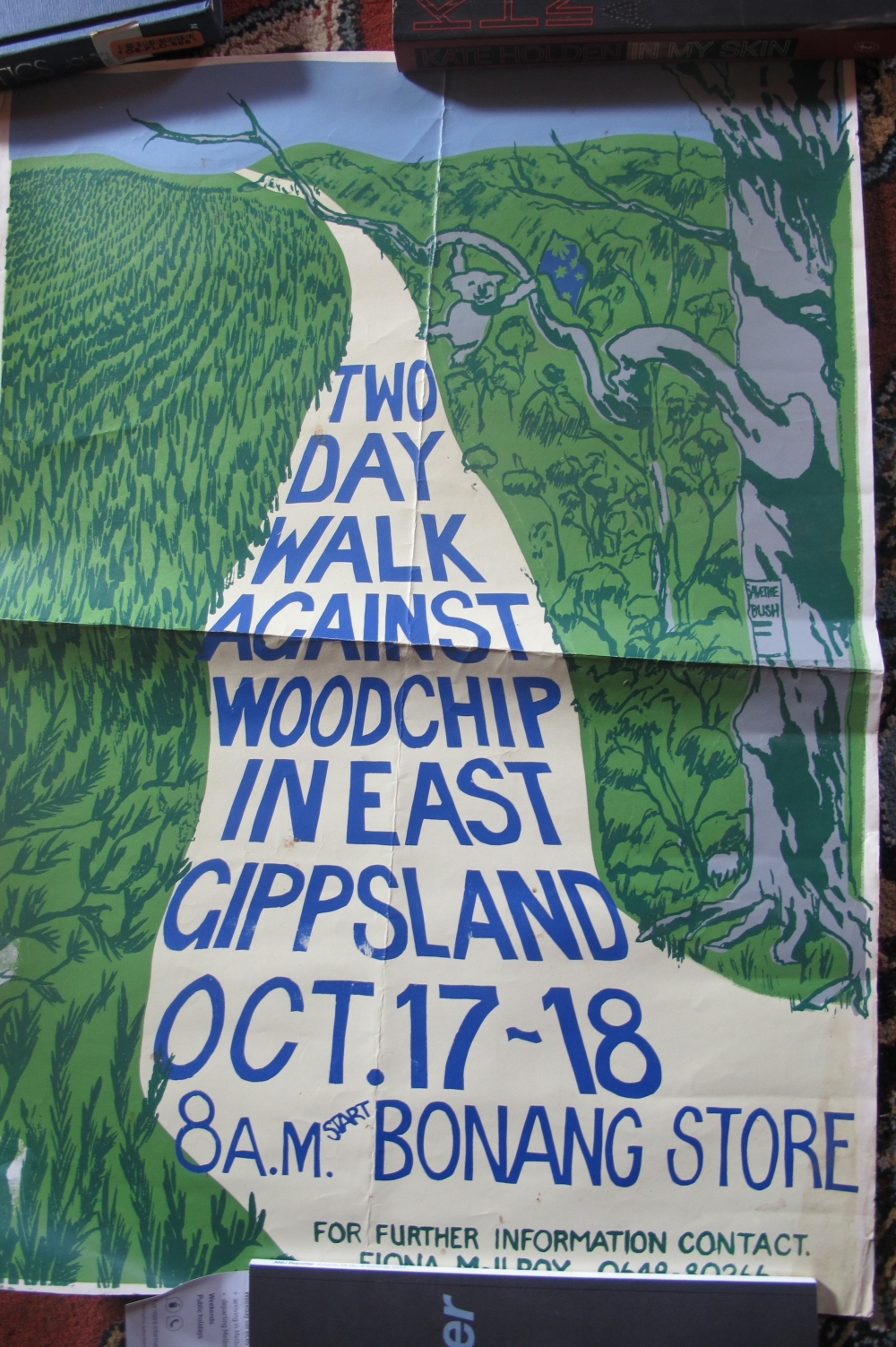

Now I do want to look back as a marker of where we have come from and might be going. In 1982 the introduction of the woodchipping industry to East Gippsland’s magnificent native forests brought together a group of concerned people. There were 50 at our first meeting but it wasn’t until later that we took a name. We deliberately chose a label usually associated with conservative values, calling ourselves the Concerned Residents of East Gippsland (CROEG).

To draw attention to the threat that woodchipping posed to our forests, we organised a two day walk down Yalmy Road, in 1981 I think, starting at Bonang and ending at Goongerah. We were lucky to have organisers el supremo, Jurg Hepp, Bob McIlroy, Will Cramer, Fiona McIlroy – and others too numerous to remember – and good weather so it went well. We found the big tree on Monkey-top track. In those days there was much more forest still intact.

The coup de grace was the presence of Judith Wright and Nugget Coombs who joined us for the end of the walk from Mt Jersey Track and for dinner at Goongerah Hall where we watched some films from up on NSW North Coast (it was from one of these that we took our title) and heard the speech below delivered by Judith.

I have no doubt that she adapted this speech for a number of events – but I believe she wrote the first version for our event. Thirty-five years later, it is still relevant.

By the way, that was the first Forest Forever camp, which has been going for 35 years organised by CROEG, then our successor, EEG, and now VNPA.

Will sense come to those who manage forests in 2018? Probably not but the politics might require it.

Read this and think for yourself, ‘What has changed?’

Enjoy Judith – and happy 2018.

Our trees protect us…

Judith Wright – 1981

Three versions of “Trees protect us–protect them”, conservation addresses in Queensland and Victoria, 1981, each about 9 pages (NLA entry)

Before I begin on the theme that trees protect us, I think it would be useful to outline the history of the movement to protect trees, so far as I’ve been involved in it. It begins, of course, a long way before my entrance on the scene – with the achievement of a few people, a number of decades ago, in convincing State governments that it would be wise and practicable to introduce legislation to make National Parks, as well as state forests, and to provide reserves as well where certain especially spectacular or important tree species could not be taken by sawmillers. These first steps to recognize the right of trees to survive and of people to enjoy them were not easily or lightly taken. The work of national parks associations and the like went much against the grain of governments and departments concerned with timber-getting.

And those national parks which were declared were always in danger of being revoked in favour of the interests of commercial timber-users. Only when, with the end of the Great Depression and the war which followed it, tourism became an important factor in the national economy, did the parks become popular at last. But well before that, those few parks (which had of course mostly been declared in areas nobody wanted for anything else) had proved their worth in protecting steep hillsides from erosion, protecting lowlands from the worst effects of flooding, and keeping major catchment areas from water pollution and turbidity. The Lamington National in Queensland, for instance, not only attracts many thousands of tourists but helps keep their water supplies clear and clean, controls flooding which probably would otherwise have long ago washed the Gold Coast out to sea, and provides a backdrop for that coast which is a joy to look at. Yet the battle to convince the then State government that a national park would be the best use for those steep slopes and high plateaux took one or two people and their supporters many years of hard work. So did the battle for practically every other nation al park ever declared in Australia. For we have always regarded trees, not just as expendable standing cellulose (a forester’s phrase, that one), but as enemies – an attitude left over from times when pastoralists and farmers sought to remove as many trees as possible to allow every acre they held to support as many sheep ore cattle as it possibly could.

Towards the end of the ‘sixties and in the beginning of the ‘seventies, a second battle to protect trees began. It involved, for the first time, a confrontation of a serious kind between people and the foresters to whom they had delegated the care of the publicly owned forests. Until then, Forestry commissions and departments had been relatively minor in influence, and their operations had been chiefly confined to manage the few forests left them after the attacks of ringbarking teams, fencers, farmers and graziers and the other tree users who had no responsibility to see that trees survived. Foresters saw themselves as the conservers of trees, and saw the rest of us as their exploiters. They were responsible for ensuring that loggers and sawmillers should have a continuing supply of timber – which would certainly not have happened if loggers and sawmillers had not been restrained from taking the lot.

This conservative management was altered very suddenly, when in the late ‘sixties Japanese interests moved into Tasmania and set up a woodchipping industry for export to their own mills. Woodchipping was something new in Australia, an operation on the same sweeping scale as open-cut mining. It became necessary to work out quite new theories on the regeneration of clear-felled forest species, and since theories were needed, they came into existence, and were hotly defended as facts.

At that time, I was president of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland; and if you wonder why Queensland’s native forests have not yet become the subject of a woodchip industry I can tell you why. Firstly, although Queensland has vast forests still, it also had a very extensive system of pine plantations, for while much of the so-called wallum country near the coast had been cleared and planted by enthusiastic foresters, and these weren’t yet ready for the woodchip industry. They are now, however, and one will shortly begin, with a pulp mill over whose site nobody can yet agree. Secondly, much of the forest remaining near Queensland ports, after the establishment of so much sugar-plantation, was rainforest and on steep slopes. Because of the woodchip industry’s preference to establish itself near ports, the first application for prospecting rights for such an establishment was for an area near Cairns….

Meanwhile, I had got further involved in the issue by becoming president of the NSW-based Campaign for Native Forests. This campaign, sparked off by the Harris-Daishowa woodchipping enterprise at Eden, held its inaugural meeting in February of 1973 in the Sydney Town Hall. It heard speakers from the NSW Forestry Commission and from Harris-Daishowa, in favour of the Eden project and declaring that neither the project nor its effects would be in the least bit dangerous to environmental values or to the Commission’s economics. Independent experts thought differently; so did the meeting; and a strong set of resolutions went to the newly formed Department and its Minister, who responded encouragingly. No new export licences would be granted unless it was proved that on both environmental and economic counts the proposal was clearly in the public interest, and environmental impact statements would be required in all cases. ….

By that time I had retired from the campaign, which in fact had achieved its objectives with the new requirements brought in by the Federal Government, and I had become a member of the newly appointed Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate. It was clear that its recommendations in the matter of forests would be subject of much concern to foresters and to the new enterprises of clear-felling for woodchip and for pine plantations; and when we attended the Forwood Conference in September-October 1973, the atmosphere was one of considerable anxiety and hostility to our inquiries and presence. (As indeed it had been ever since the first questioning of the clear-felling programmes.) The Committee’s report issued early in the following year in fact recommended that woodchipping and other operations involving clear-felling be discontinued until environmental effects were better known and properly assessed, that further pine planting at the expense of native forests be suspended for further research into economic and environmental justification, and that multiple use and conservative management of forests should be a primary aim for forest authorities. Some foresters privately agreed with these recommendations, indeed helped us formulate them; for others they were anathema.

Since that time, the EIS (Environmental Impact Statement) legislation has been subject to insidious erosion, and the exercise of Federal government powers to prevent the export of materials where this is decided not to be in the national interest has been used only in the case of the sandmining of Fraser Island (a praiseworthy exercise, but it should not be sole of its kind.) Now. I seem to be coming back into the arena of the forests, with the clear-felling and woodchipping arguments being revived on practically the same lines as before, I have at least one governmental sanction for this talk, in the Commonwealth’s rather ironic slogan for World Environment Day – ‘Our trees protect us – conserve them’. But it is not a slogan the States are likely to welcome; in Victoria particularly, the arena for woodchipping has shifted from the wrecked forests of Eden to the East Gippsland area. And the EIS on the Gippsland forests and on the proposed pulpmill will not indicate that these are areas where the national interest demands a ban on an export licence.

I quote from a paper lately given by a Victorian (not a forester) on the state and future of our native forests (J.R.J. French): “In Australia we are overcutting our native forests, and moving towards fast-grown, short rotation eucalypt plantations, and exotic pines for future sawlogs, with native forests seen as major woodchip and wood pulp resources by the forestry planners…. Environmental Impact Statements are mere smoke-screens, as we have little information on E.G. forests, either before, during or after such large-scale operations. This ‘plethora of problems’ suggests that the time has come when a forest will be valued as much for its life-support capacity, as for its yield of products and services. By life-support I refer to the role of forests… in maintaining the quality of air, water and food along with other energy necessary for the human civilization to survive and prosper.” As he adds, until now it has been timber production which has been seen as the main function of public forests. Apart from objecting that it might well be that trees and forests have rights of their own to exist, apart from those of being ‘necessary to human civilization’, this seems a fair statement of the case. And an overdue one.

I lately visited the Errinundra Block, just south of the NSW border in north-eastern Victoria – an area now at extreme risk, if not already committed, to the woodchipping program. I had heard of this area back in 1973, when the Campaign for Native Forests had a letter from an inhabitant of Bairnsdale, saying that woodchipping industry representatives had been visiting private landholders in the southern Monaro and in far north-eastern Victoria, offering a down-payment on their timber – to be taken at some later unspecified date. …

I went to the Errinundra Block under the guidance of local people and relatives of my own, who were already involved in the issue of the forests. They showed me not only the areas of past selective logging, which appeared to have recovered very well, but a large area of past clear-felling where eucalypt and other regrowth have evidently never been thinned or managed – so that their small thin stems are crowded to the point of impenetrability to a height of two or three metres – an area of wreck where a whole small valley has been poisoned from the air with one of those defoliants which end by killing or crippling the users; a reserve in which sassafras and shining gum reach splendid health and proportions’ and an area adjoining the forest proper where clear-felling for woodchip on private land has left the usual tragic sight of bared torn-up soil bordered by burned tree-trunks pushed into the nearest stream-bed and left to rot. We looked at the steep slopes which drop south into the river valleys of the Bemm, the Cann, the Brodribb and the Errinundra, now clothed with protective forest cover which holds the soils from descending en masse into the rivers. We saw that already along the logging roads blackberries are growing and rabbits have penetrated everywhere; such weed and animal pests will certainly increase with further exploitation.

Now the Conservation Land Council’s report of 1974 on the area states that soils are generally granitic, or sedimentary. The cover in the Errinundra block, though selectively logged for many years, remains dense enough to have kept erosion low except for some rilling – which will certainly turn into gullying and tunnelling if left bare for long enough. “Once the native vegetation is removed”, says the Council’s report, “severe water erosion can occur quickly because of the high and often intensive rainfall. The hazard is greatest in the largely uncleared mountainous two-thirds of the area because of its steep slopes.” It is here that the new application for woodchipping is made.

There can be no doubt that a woodchipping industry in this area could be even more destructive than that at Eden has proved to be – and to anyone who has seen that area, with its silted streams, rivers and lakes, its polluted estuary and port, its eroded slopes and gullied roadsides, its pathetically raped aspect. And the blackened areas where fires have spread from dumps of waste bark to destroy large areas of timber and national parkland, the prospect of the loss of the Errinundra forest to similar forces is evil indeed. There is little settlement in the area – it formerly supported three sawmills, but now – because of the loss of private forests to the machinations of the woodchippers and foresters – has only one; but the rivers below it and the farms of eastern Gippsland are largely protected by those forested slopes from severe flooding. To bare them would increase water heights, velocity and turbidity, and therefore erosion and the flooding of farmlands.

Says the Institute of Foresters of Australia in its statement on the use of forests for woodchip production: “ The use of forested lands to support large projects such as the export of woodchips has important environmental, social and economic consequences…” Decision-makers should “take account of alternative forms of forest use, and weigh their direct and indirect costs and benefits in terms of community welfare, economic gain and national interest. The benefits to be considered must include all those production, protection, recreational, aesthetic and scientific values which forests provide.” The Land Conservation Council’s report on the area asserted that nature conservation is a high priority in Errinundra, with its range of forested habitats, its variety of slopes and aspects, its ‘very high quality timber’ of shining gum, mountain grey gum, messmate, cut-tail, sassafras and the scientifically interesting easternmost occurrences of alpine ash, as well as a rare stand of mountain plum pine and the forest of the Goonmirk Rocks area which is so splendid that it seems fire has not reached it for many hundreds of years. Its wildlife includes the bobuck (trichosurus caninus), the ground parrot, the eastern bristle-bird and others, becoming rare; its ferntree and sassafras gullies are splendid. Its rainfall goes as high as 2000 mm and its growing season is long – which is why there is so far little erosion.

Now, if the Commonwealth were to take seriously its injunction to conserve the trees that protect us, the Errinundra forest would be a prime candidate for protection and no export licence could possibly be granted over a woodchip operation there. The situation in which the Tasmanian forests and that at Eden were sold off to Japanese interests without the least pretence at research into or knowledge of the effects of such wholesale operations on soils, rainfall, wildlife, adjoining farmland, tree species or regeneration rates, no longer applies. We have at least, now, Commonwealth legislation requiring environmental impact statements and the condition that both economically and environmentally the project shall be judged to be in the ‘national interest’ before export licences are issued; we also have the Victorian Environment Effects Act of 1978 and the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. This should make it a far cry from the conditions under which Tasmania and Eden were committed to the bulldozers. But does it?…

Economically, woodchipping has been ruinously priced, not to the buyer but to the seller. As the Routleys’ book The fight for the forests proved, if environmental costs had been included in royalties payable, there could have been no woodchipping industry in Australia. Since foresters wanted jobs, and the kind of authority that goes with power, and since State governments are, to put it politely, not very bright, the bargains struck were little more rewarding to the owners of the forests – the Australian public – than a half-price clearance sale. Indeed, this is how foresters regard the woodchipping industry – as a method of ‘getting rid’ of what they call ‘degenerate forests’ in order to test out theories of regeneration and successive clearfelling which are – as honest foresters admit – no more than theories. There are already signs that projected time-scales will be too low and costs far too high. Necessary inputs of energy and fertiliser are rising in price so fast that earlier costings are going to be knocked sideways.

Environmental costs, on the other hand, have never been reckoned. They cannot be, for even on the short time-scale, they are unknown, and on the longer scale they will be cumulative far into an unknown future. Dredging of ports, silting of water supplies, flooding of farmlands, increase in weed infestation and losses by bushfires are all possible costs that won’t be charged against the woodchip industry. ….

As for employment: already sawmills around Eden are closing down for lack of sawlogs; the three mills in the Errinundra are now reduced to one because of the loss of logs from private land to the woodchipping interests of Eden. The pulpmill proposed for Bairnsdale (Orbost) will pollute important fishing areas and lessen Bairnsdale’s tourist dollars. In the long term, farmlands which support important industries will deteriorate. Nothing is to be gained from the woodchipping industry, which, as a Tasmanian once told me, is one of the most ruthless ever to move into Australia. (And that is saying something!)

I have nothing whatever to say against the Japanese decision to increase and improve its own already large forest area at the expense of other countries weak or foolish enough to sacrifice theirs. Or to export pollutive industries such as wood-pulp mills from an already highly polluted country. I do question, first, the use to which our exported wood-pulp is being put in wasteful over-packaging, and second, the refusal of Japanese interests to pay a price which will allow us to regenerate the areas already devastated in their projects. Above all, I question the arguments put forward by foresters here in their favour and the extension of present areas into new ones. The so-called degeneracy of our native forests can, I think, (and my inspection of Errinundra seems to confirm it) be put down squarely at the doors of Forestry Commissions and governments. It results from poor management, bad practice, and lack of planning of land use both overall and in particular interests. CSIRO’s latest report indicates that more than half our present pastoral and agricultural land is eroded to the point where major and highly expensive works should be undertaken to save our soils and large areas should be withdrawn from production altogether for such works; and that much o9f this deterioration can be put down to unwise clearing of forests. We can’t afford to lose any more of our protective trees. We have a responsibility to the world itself to keep our soils as productive as possible, both for food to be consumed here and for export. We have absolutely no responsibility to devote more of our very scarce forests to the bulldozer and the woodchip industry to be turned into expensive and unnecessary packaging and litter.

That is why I think it is time for Australians who have an interest in this country’s future to unite in defence of our remaining forests. If greedy and paralytic governments decide to sell out more – in the face of what even foresters admit to be drastic environmental deterioration in present project areas – we must get rid of those governments in favour of others which will act to protect and regenerate them wisely, and to protect our essential interests in soils, water and offshore fishing industries. If we do not speak now, and speak loudly and clearly, we betray our own future. The trees which protect us are in imminent danger – and their danger is our own danger.

Our trees protect us…

Judith Wright – 1981

Three versions of “Trees protect us–protect them”, conservation addresses in Queensland and Victoria, 1981, each about 9 pages (NLA entry)

Before I begin on the theme that trees protect us, I think it would be useful to outline the history of the movement to protect trees, so far as I’ve been involved in it. It begins, of course, a long way before my entrance on the scene – with the achievement of a few people, a number of decades ago, in convincing State governments that it would be wise and practicable to introduce legislation to make National Parks, as well as state forests, and to provide reserves as well where certain especially spectacular or important tree species could not be taken by sawmillers. These first steps to recognize the right of trees to survive and of people to enjoy them were not easily or lightly taken. The work of national parks associations and the like went much against the grain of governments and departments concerned with timber-getting.

And those national parks which were declared were always in danger of being revoked in favour of the interests of commercial timber-users. Only when, with the end of the Great Depression and the war which followed it, tourism became an important factor in the national economy, did the parks become popular at last. But well before that, those few parks (which had of course mostly been declared in areas nobody wanted for anything else) had proved their worth in protecting steep hillsides from erosion, protecting lowlands from the worst effects of flooding, and keeping major catchment areas from water pollution and turbidity. The Lamington National in Queensland, for instance, not only attracts many thousands of tourists but helps keep their water supplies clear and clean, controls flooding which probably would otherwise have long ago washed the Gold Coast out to sea, and provides a backdrop for that coast which is a joy to look at. Yet the battle to convince the then State government that a national park would be the best use for those steep slopes and high plateaux took one or two people and their supporters many years of hard work. So did the battle for practically every other nation al park ever declared in Australia. For we have always regarded trees, not just as expendable standing cellulose (a forester’s phrase, that one), but as enemies – an attitude left over from times when pastoralists and farmers sought to remove as many trees as possible to allow every acre they held to support as many sheep ore cattle as it possibly could.

Towards the end of the ‘sixties and in the beginning of the ‘seventies, a second battle to protect trees began. It involved, for the first time, a confrontation of a serious kind between people and the foresters to whom they had delegated the care of the publicly owned forests. Until then, Forestry commissions and departments had been relatively minor in influence, and their operations had been chiefly confined to manage the few forests left them after the attacks of ringbarking teams, fencers, farmers and graziers and the other tree users who had no responsibility to see that trees survived. Foresters saw themselves as the conservers of trees, and saw the rest of us as their exploiters. They were responsible for ensuring that loggers and sawmillers should have a continuing supply of timber – which would certainly not have happened if loggers and sawmillers had not been restrained from taking the lot.

This conservative management was altered very suddenly, when in the late ‘sixties Japanese interests moved into Tasmania and set up a woodchipping industry for export to their own mills. Woodchipping was something new in Australia, an operation on the same sweeping scale as open-cut mining. It became necessary to work out quite new theories on the regeneration of clear-felled forest species, and since theories were needed, they came into existence, and were hotly defended as facts.

At that time, I was president of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland; and if you wonder why Queensland’s native forests have not yet become the subject of a woodchip industry I can tell you why. Firstly, although Queensland has vast forests still, it also had a very extensive system of pine plantations, for while much of the so-called wallum country near the coast had been cleared and planted by enthusiastic foresters, and these weren’t yet ready for the woodchip industry. They are now, however, and one will shortly begin, with a pulp mill over whose site nobody can yet agree. Secondly, much of the forest remaining near Queensland ports, after the establishment of so much sugar-plantation, was rainforest and on steep slopes. Because of the woodchip industry’s preference to establish itself near ports, the first application for prospecting rights for such an establishment was for an area near Cairns….

Meanwhile, I had got further involved in the issue by becoming president of the NSW-based Campaign for Native Forests. This campaign, sparked off by the Harris-Daishowa woodchipping enterprise at Eden, held its inaugural meeting in February of 1973 in the Sydney Town Hall. It heard speakers from the NSW Forestry Commission and from Harris-Daishowa, in favour of the Eden project and declaring that neither the project nor its effects would be in the least bit dangerous to environmental values or to the Commission’s economics. Independent experts thought differently; so did the meeting; and a strong set of resolutions went to the newly formed Department and its Minister, who responded encouragingly. No new export licences would be granted unless it was proved that on both environmental and economic counts the proposal was clearly in the public interest, and environmental impact statements would be required in all cases. ….

By that time I had retired from the campaign, which in fact had achieved its objectives with the new requirements brought in by the Federal Government, and I had become a member of the newly appointed Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate. It was clear that its recommendations in the matter of forests would be subject of much concern to foresters and to the new enterprises of clear-felling for woodchip and for pine plantations; and when we attended the Forwood Conference in September-October 1973, the atmosphere was one of considerable anxiety and hostility to our inquiries and presence. (As indeed it had been ever since the first questioning of the clear-felling programmes.) The Committee’s report issued early in the following year in fact recommended that woodchipping and other operations involving clear-felling be discontinued until environmental effects were better known and properly assessed, that further pine planting at the expense of native forests be suspended for further research into economic and environmental justification, and that multiple use and conservative management of forests should be a primary aim for forest authorities. Some foresters privately agreed with these recommendations, indeed helped us formulate them; for others they were anathema.

Since that time, the EIS (Environmental Impact Statement) legislation has been subject to insidious erosion, and the exercise of Federal government powers to prevent the export of materials where this is decided not to be in the national interest has been used only in the case of the sandmining of Fraser Island (a praiseworthy exercise, but it should not be sole of its kind.) Now. I seem to be coming back into the arena of the forests, with the clear-felling and woodchipping arguments being revived on practically the same lines as before, I have at least one governmental sanction for this talk, in the Commonwealth’s rather ironic slogan for World Environment Day – ‘Our trees protect us – conserve them’. But it is not a slogan the States are likely to welcome; in Victoria particularly, the arena for woodchipping has shifted from the wrecked forests of Eden to the East Gippsland area. And the EIS on the Gippsland forests and on the proposed pulpmill will not indicate that these are areas where the national interest demands a ban on an export licence.

I quote from a paper lately given by a Victorian (not a forester) on the state and future of our native forests (J.R.J. French): “In Australia we are overcutting our native forests, and moving towards fast-grown, short rotation eucalypt plantations, and exotic pines for future sawlogs, with native forests seen as major woodchip and wood pulp resources by the forestry planners…. Environmental Impact Statements are mere smoke-screens, as we have little information on E.G. forests, either before, during or after such large-scale operations. This ‘plethora of problems’ suggests that the time has come when a forest will be valued as much for its life-support capacity, as for its yield of products and services. By life-support I refer to the role of forests… in maintaining the quality of air, water and food along with other energy necessary for the human civilization to survive and prosper.” As he adds, until now it has been timber production which has been seen as the main function of public forests. Apart from objecting that it might well be that trees and forests have rights of their own to exist, apart from those of being ‘necessary to human civilization’, this seems a fair statement of the case. And an overdue one.

I lately visited the Errinundra Block, just south of the NSW border in north-eastern Victoria – an area now at extreme risk, if not already committed, to the woodchipping program. I had heard of this area back in 1973, when the Campaign for Native Forests had a letter from an inhabitant of Bairnsdale, saying that woodchipping industry representatives had been visiting private landholders in the southern Monaro and in far north-eastern Victoria, offering a down-payment on their timber – to be taken at some later unspecified date. …

I went to the Errinundra Block under the guidance of local people and relatives of my own, who were already involved in the issue of the forests. They showed me not only the areas of past selective logging, which appeared to have recovered very well, but a large area of past clear-felling where eucalypt and other regrowth have evidently never been thinned or managed – so that their small thin stems are crowded to the point of impenetrability to a height of two or three metres – an area of wreck where a whole small valley has been poisoned from the air with one of those defoliants which end by killing or crippling the users; a reserve in which sassafras and shining gum reach splendid health and proportions’ and an area adjoining the forest proper where clear-felling for woodchip on private land has left the usual tragic sight of bared torn-up soil bordered by burned tree-trunks pushed into the nearest stream-bed and left to rot. We looked at the steep slopes which drop south into the river valleys of the Bemm, the Cann, the Brodribb and the Errinundra, now clothed with protective forest cover which holds the soils from descending en masse into the rivers. We saw that already along the logging roads blackberries are growing and rabbits have penetrated everywhere; such weed and animal pests will certainly increase with further exploitation.

Now the Conservation Land Council’s report of 1974 on the area states that soils are generally granitic, or sedimentary. The cover in the Errinundra block, though selectively logged for many years, remains dense enough to have kept erosion low except for some rilling – which will certainly turn into gullying and tunnelling if left bare for long enough. “Once the native vegetation is removed”, says the Council’s report, “severe water erosion can occur quickly because of the high and often intensive rainfall. The hazard is greatest in the largely uncleared mountainous two-thirds of the area because of its steep slopes.” It is here that the new application for woodchipping is made.

There can be no doubt that a woodchipping industry in this area could be even more destructive than that at Eden has proved to be – and to anyone who has seen that area, with its silted streams, rivers and lakes, its polluted estuary and port, its eroded slopes and gullied roadsides, its pathetically raped aspect. And the blackened areas where fires have spread from dumps of waste bark to destroy large areas of timber and national parkland, the prospect of the loss of the Errinundra forest to similar forces is evil indeed. There is little settlement in the area – it formerly supported three sawmills, but now – because of the loss of private forests to the machinations of the woodchippers and foresters – has only one; but the rivers below it and the farms of eastern Gippsland are largely protected by those forested slopes from severe flooding. To bare them would increase water heights, velocity and turbidity, and therefore erosion and the flooding of farmlands.

Says the Institute of Foresters of Australia in its statement on the use of forests for woodchip production: “ The use of forested lands to support large projects such as the export of woodchips has important environmental, social and economic consequences…” Decision-makers should “take account of alternative forms of forest use, and weigh their direct and indirect costs and benefits in terms of community welfare, economic gain and national interest. The benefits to be considered must include all those production, protection, recreational, aesthetic and scientific values which forests provide.” The Land Conservation Council’s report on the area asserted that nature conservation is a high priority in Errinundra, with its range of forested habitats, its variety of slopes and aspects, its ‘very high quality timber’ of shining gum, mountain grey gum, messmate, cut-tail, sassafras and the scientifically interesting easternmost occurrences of alpine ash, as well as a rare stand of mountain plum pine and the forest of the Goonmirk Rocks area which is so splendid that it seems fire has not reached it for many hundreds of years. Its wildlife includes the bobuck (trichosurus caninus), the ground parrot, the eastern bristle-bird and others, becoming rare; its ferntree and sassafras gullies are splendid. Its rainfall goes as high as 2000 mm and its growing season is long – which is why there is so far little erosion.

Now, if the Commonwealth were to take seriously its injunction to conserve the trees that protect us, the Errinundra forest would be a prime candidate for protection and no export licence could possibly be granted over a woodchip operation there. The situation in which the Tasmanian forests and that at Eden were sold off to Japanese interests without the least pretence at research into or knowledge of the effects of such wholesale operations on soils, rainfall, wildlife, adjoining farmland, tree species or regeneration rates, no longer applies. We have at least, now, Commonwealth legislation requiring environmental impact statements and the condition that both economically and environmentally the project shall be judged to be in the ‘national interest’ before export licences are issued; we also have the Victorian Environment Effects Act of 1978 and the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. This should make it a far cry from the conditions under which Tasmania and Eden were committed to the bulldozers. But does it?…

Economically, woodchipping has been ruinously priced, not to the buyer but to the seller. As the Routleys’ book The fight for the forests proved, if environmental costs had been included in royalties payable, there could have been no woodchipping industry in Australia. Since foresters wanted jobs, and the kind of authority that goes with power, and since State governments are, to put it politely, not very bright, the bargains struck were little more rewarding to the owners of the forests – the Australian public – than a half-price clearance sale. Indeed, this is how foresters regard the woodchipping industry – as a method of ‘getting rid’ of what they call ‘degenerate forests’ in order to test out theories of regeneration and successive clearfelling which are – as honest foresters admit – no more than theories. There are already signs that projected time-scales will be too low and costs far too high. Necessary inputs of energy and fertiliser are rising in price so fast that earlier costings are going to be knocked sideways.

Environmental costs, on the other hand, have never been reckoned. They cannot be, for even on the short time-scale, they are unknown, and on the longer scale they will be cumulative far into an unknown future. Dredging of ports, silting of water supplies, flooding of farmlands, increase in weed infestation and losses by bushfires are all possible costs that won’t be charged against the woodchip industry. ….

As for employment: already sawmills around Eden are closing down for lack of sawlogs; the three mills in the Errinundra are now reduced to one because of the loss of logs from private land to the woodchipping interests of Eden. The pulpmill proposed for Bairnsdale (Orbost) will pollute important fishing areas and lessen Bairnsdale’s tourist dollars. In the long term, farmlands which support important industries will deteriorate. Nothing is to be gained from the woodchipping industry, which, as a Tasmanian once told me, is one of the most ruthless ever to move into Australia. (And that is saying something!)

I have nothing whatever to say against the Japanese decision to increase and improve its own already large forest area at the expense of other countries weak or foolish enough to sacrifice theirs. Or to export pollutive industries such as wood-pulp mills from an already highly polluted country. I do question, first, the use to which our exported wood-pulp is being put in wasteful over-packaging, and second, the refusal of Japanese interests to pay a price which will allow us to regenerate the areas already devastated in their projects. Above all, I question the arguments put forward by foresters here in their favour and the extension of present areas into new ones. The so-called degeneracy of our native forests can, I think, (and my inspection of Errinundra seems to confirm it) be put down squarely at the doors of Forestry Commissions and governments. It results from poor management, bad practice, and lack of planning of land use both overall and in particular interests. CSIRO’s latest report indicates that more than half our present pastoral and agricultural land is eroded to the point where major and highly expensive works should be undertaken to save our soils and large areas should be withdrawn from production altogether for such works; and that much o9f this deterioration can be put down to unwise clearing of forests. We can’t afford to lose any more of our protective trees. We have a responsibility to the world itself to keep our soils as productive as possible, both for food to be consumed here and for export. We have absolutely no responsibility to devote more of our very scarce forests to the bulldozer and the woodchip industry to be turned into expensive and unnecessary packaging and litter.

That is why I think it is time for Australians who have an interest in this country’s future to unite in defence of our remaining forests. If greedy and paralytic governments decide to sell out more – in the face of what even foresters admit to be drastic environmental deterioration in present project areas – we must get rid of those governments in favour of others which will act to protect and regenerate them wisely, and to protect our essential interests in soils, water and offshore fishing industries. If we do not speak now, and speak loudly and clearly, we betray our own future. The trees which protect us are in imminent danger – and their danger is our own danger.

Our trees protect us…

Judith Wright – 1981

Three versions of “Trees protect us–protect them”, conservation addresses in Queensland and Victoria, 1981, each about 9 pages (NLA entry)

Before I begin on the theme that trees protect us, I think it would be useful to outline the history of the movement to protect trees, so far as I’ve been involved in it. It begins, of course, a long way before my entrance on the scene – with the achievement of a few people, a number of decades ago, in convincing State governments that it would be wise and practicable to introduce legislation to make National Parks, as well as state forests, and to provide reserves as well where certain especially spectacular or important tree species could not be taken by sawmillers. These first steps to recognize the right of trees to survive and of people to enjoy them were not easily or lightly taken. The work of national parks associations and the like went much against the grain of governments and departments concerned with timber-getting.

And those national parks which were declared were always in danger of being revoked in favour of the interests of commercial timber-users. Only when, with the end of the Great Depression and the war which followed it, tourism became an important factor in the national economy, did the parks become popular at last. But well before that, those few parks (which had of course mostly been declared in areas nobody wanted for anything else) had proved their worth in protecting steep hillsides from erosion, protecting lowlands from the worst effects of flooding, and keeping major catchment areas from water pollution and turbidity. The Lamington National in Queensland, for instance, not only attracts many thousands of tourists but helps keep their water supplies clear and clean, controls flooding which probably would otherwise have long ago washed the Gold Coast out to sea, and provides a backdrop for that coast which is a joy to look at. Yet the battle to convince the then State government that a national park would be the best use for those steep slopes and high plateaux took one or two people and their supporters many years of hard work. So did the battle for practically every other nation al park ever declared in Australia. For we have always regarded trees, not just as expendable standing cellulose (a forester’s phrase, that one), but as enemies – an attitude left over from times when pastoralists and farmers sought to remove as many trees as possible to allow every acre they held to support as many sheep ore cattle as it possibly could.

Towards the end of the ‘sixties and in the beginning of the ‘seventies, a second battle to protect trees began. It involved, for the first time, a confrontation of a serious kind between people and the foresters to whom they had delegated the care of the publicly owned forests. Until then, Forestry commissions and departments had been relatively minor in influence, and their operations had been chiefly confined to manage the few forests left them after the attacks of ringbarking teams, fencers, farmers and graziers and the other tree users who had no responsibility to see that trees survived. Foresters saw themselves as the conservers of trees, and saw the rest of us as their exploiters. They were responsible for ensuring that loggers and sawmillers should have a continuing supply of timber – which would certainly not have happened if loggers and sawmillers had not been restrained from taking the lot.

This conservative management was altered very suddenly, when in the late ‘sixties Japanese interests moved into Tasmania and set up a woodchipping industry for export to their own mills. Woodchipping was something new in Australia, an operation on the same sweeping scale as open-cut mining. It became necessary to work out quite new theories on the regeneration of clear-felled forest species, and since theories were needed, they came into existence, and were hotly defended as facts.

At that time, I was president of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland; and if you wonder why Queensland’s native forests have not yet become the subject of a woodchip industry I can tell you why. Firstly, although Queensland has vast forests still, it also had a very extensive system of pine plantations, for while much of the so-called wallum country near the coast had been cleared and planted by enthusiastic foresters, and these weren’t yet ready for the woodchip industry. They are now, however, and one will shortly begin, with a pulp mill over whose site nobody can yet agree. Secondly, much of the forest remaining near Queensland ports, after the establishment of so much sugar-plantation, was rainforest and on steep slopes. Because of the woodchip industry’s preference to establish itself near ports, the first application for prospecting rights for such an establishment was for an area near Cairns….

Meanwhile, I had got further involved in the issue by becoming president of the NSW-based Campaign for Native Forests. This campaign, sparked off by the Harris-Daishowa woodchipping enterprise at Eden, held its inaugural meeting in February of 1973 in the Sydney Town Hall. It heard speakers from the NSW Forestry Commission and from Harris-Daishowa, in favour of the Eden project and declaring that neither the project nor its effects would be in the least bit dangerous to environmental values or to the Commission’s economics. Independent experts thought differently; so did the meeting; and a strong set of resolutions went to the newly formed Department and its Minister, who responded encouragingly. No new export licences would be granted unless it was proved that on both environmental and economic counts the proposal was clearly in the public interest, and environmental impact statements would be required in all cases. ….

By that time I had retired from the campaign, which in fact had achieved its objectives with the new requirements brought in by the Federal Government, and I had become a member of the newly appointed Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate. It was clear that its recommendations in the matter of forests would be subject of much concern to foresters and to the new enterprises of clear-felling for woodchip and for pine plantations; and when we attended the Forwood Conference in September-October 1973, the atmosphere was one of considerable anxiety and hostility to our inquiries and presence. (As indeed it had been ever since the first questioning of the clear-felling programmes.) The Committee’s report issued early in the following year in fact recommended that woodchipping and other operations involving clear-felling be discontinued until environmental effects were better known and properly assessed, that further pine planting at the expense of native forests be suspended for further research into economic and environmental justification, and that multiple use and conservative management of forests should be a primary aim for forest authorities. Some foresters privately agreed with these recommendations, indeed helped us formulate them; for others they were anathema.

Since that time, the EIS (Environmental Impact Statement) legislation has been subject to insidious erosion, and the exercise of Federal government powers to prevent the export of materials where this is decided not to be in the national interest has been used only in the case of the sandmining of Fraser Island (a praiseworthy exercise, but it should not be sole of its kind.) Now. I seem to be coming back into the arena of the forests, with the clear-felling and woodchipping arguments being revived on practically the same lines as before, I have at least one governmental sanction for this talk, in the Commonwealth’s rather ironic slogan for World Environment Day – ‘Our trees protect us – conserve them’. But it is not a slogan the States are likely to welcome; in Victoria particularly, the arena for woodchipping has shifted from the wrecked forests of Eden to the East Gippsland area. And the EIS on the Gippsland forests and on the proposed pulpmill will not indicate that these are areas where the national interest demands a ban on an export licence.

I quote from a paper lately given by a Victorian (not a forester) on the state and future of our native forests (J.R.J. French): “In Australia we are overcutting our native forests, and moving towards fast-grown, short rotation eucalypt plantations, and exotic pines for future sawlogs, with native forests seen as major woodchip and wood pulp resources by the forestry planners…. Environmental Impact Statements are mere smoke-screens, as we have little information on E.G. forests, either before, during or after such large-scale operations. This ‘plethora of problems’ suggests that the time has come when a forest will be valued as much for its life-support capacity, as for its yield of products and services. By life-support I refer to the role of forests… in maintaining the quality of air, water and food along with other energy necessary for the human civilization to survive and prosper.” As he adds, until now it has been timber production which has been seen as the main function of public forests. Apart from objecting that it might well be that trees and forests have rights of their own to exist, apart from those of being ‘necessary to human civilization’, this seems a fair statement of the case. And an overdue one.

I lately visited the Errinundra Block, just south of the NSW border in north-eastern Victoria – an area now at extreme risk, if not already committed, to the woodchipping program. I had heard of this area back in 1973, when the Campaign for Native Forests had a letter from an inhabitant of Bairnsdale, saying that woodchipping industry representatives had been visiting private landholders in the southern Monaro and in far north-eastern Victoria, offering a down-payment on their timber – to be taken at some later unspecified date. …

I went to the Errinundra Block under the guidance of local people and relatives of my own, who were already involved in the issue of the forests. They showed me not only the areas of past selective logging, which appeared to have recovered very well, but a large area of past clear-felling where eucalypt and other regrowth have evidently never been thinned or managed – so that their small thin stems are crowded to the point of impenetrability to a height of two or three metres – an area of wreck where a whole small valley has been poisoned from the air with one of those defoliants which end by killing or crippling the users; a reserve in which sassafras and shining gum reach splendid health and proportions’ and an area adjoining the forest proper where clear-felling for woodchip on private land has left the usual tragic sight of bared torn-up soil bordered by burned tree-trunks pushed into the nearest stream-bed and left to rot. We looked at the steep slopes which drop south into the river valleys of the Bemm, the Cann, the Brodribb and the Errinundra, now clothed with protective forest cover which holds the soils from descending en masse into the rivers. We saw that already along the logging roads blackberries are growing and rabbits have penetrated everywhere; such weed and animal pests will certainly increase with further exploitation.

Now the Conservation Land Council’s report of 1974 on the area states that soils are generally granitic, or sedimentary. The cover in the Errinundra block, though selectively logged for many years, remains dense enough to have kept erosion low except for some rilling – which will certainly turn into gullying and tunnelling if left bare for long enough. “Once the native vegetation is removed”, says the Council’s report, “severe water erosion can occur quickly because of the high and often intensive rainfall. The hazard is greatest in the largely uncleared mountainous two-thirds of the area because of its steep slopes.” It is here that the new application for woodchipping is made.

There can be no doubt that a woodchipping industry in this area could be even more destructive than that at Eden has proved to be – and to anyone who has seen that area, with its silted streams, rivers and lakes, its polluted estuary and port, its eroded slopes and gullied roadsides, its pathetically raped aspect. And the blackened areas where fires have spread from dumps of waste bark to destroy large areas of timber and national parkland, the prospect of the loss of the Errinundra forest to similar forces is evil indeed. There is little settlement in the area – it formerly supported three sawmills, but now – because of the loss of private forests to the machinations of the woodchippers and foresters – has only one; but the rivers below it and the farms of eastern Gippsland are largely protected by those forested slopes from severe flooding. To bare them would increase water heights, velocity and turbidity, and therefore erosion and the flooding of farmlands.

Says the Institute of Foresters of Australia in its statement on the use of forests for woodchip production: “ The use of forested lands to support large projects such as the export of woodchips has important environmental, social and economic consequences…” Decision-makers should “take account of alternative forms of forest use, and weigh their direct and indirect costs and benefits in terms of community welfare, economic gain and national interest. The benefits to be considered must include all those production, protection, recreational, aesthetic and scientific values which forests provide.” The Land Conservation Council’s report on the area asserted that nature conservation is a high priority in Errinundra, with its range of forested habitats, its variety of slopes and aspects, its ‘very high quality timber’ of shining gum, mountain grey gum, messmate, cut-tail, sassafras and the scientifically interesting easternmost occurrences of alpine ash, as well as a rare stand of mountain plum pine and the forest of the Goonmirk Rocks area which is so splendid that it seems fire has not reached it for many hundreds of years. Its wildlife includes the bobuck (trichosurus caninus), the ground parrot, the eastern bristle-bird and others, becoming rare; its ferntree and sassafras gullies are splendid. Its rainfall goes as high as 2000 mm and its growing season is long – which is why there is so far little erosion.

Now, if the Commonwealth were to take seriously its injunction to conserve the trees that protect us, the Errinundra forest would be a prime candidate for protection and no export licence could possibly be granted over a woodchip operation there. The situation in which the Tasmanian forests and that at Eden were sold off to Japanese interests without the least pretence at research into or knowledge of the effects of such wholesale operations on soils, rainfall, wildlife, adjoining farmland, tree species or regeneration rates, no longer applies. We have at least, now, Commonwealth legislation requiring environmental impact statements and the condition that both economically and environmentally the project shall be judged to be in the ‘national interest’ before export licences are issued; we also have the Victorian Environment Effects Act of 1978 and the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. This should make it a far cry from the conditions under which Tasmania and Eden were committed to the bulldozers. But does it?…

Economically, woodchipping has been ruinously priced, not to the buyer but to the seller. As the Routleys’ book The fight for the forests proved, if environmental costs had been included in royalties payable, there could have been no woodchipping industry in Australia. Since foresters wanted jobs, and the kind of authority that goes with power, and since State governments are, to put it politely, not very bright, the bargains struck were little more rewarding to the owners of the forests – the Australian public – than a half-price clearance sale. Indeed, this is how foresters regard the woodchipping industry – as a method of ‘getting rid’ of what they call ‘degenerate forests’ in order to test out theories of regeneration and successive clearfelling which are – as honest foresters admit – no more than theories. There are already signs that projected time-scales will be too low and costs far too high. Necessary inputs of energy and fertiliser are rising in price so fast that earlier costings are going to be knocked sideways.

Environmental costs, on the other hand, have never been reckoned. They cannot be, for even on the short time-scale, they are unknown, and on the longer scale they will be cumulative far into an unknown future. Dredging of ports, silting of water supplies, flooding of farmlands, increase in weed infestation and losses by bushfires are all possible costs that won’t be charged against the woodchip industry. ….

As for employment: already sawmills around Eden are closing down for lack of sawlogs; the three mills in the Errinundra are now reduced to one because of the loss of logs from private land to the woodchipping interests of Eden. The pulpmill proposed for Bairnsdale (Orbost) will pollute important fishing areas and lessen Bairnsdale’s tourist dollars. In the long term, farmlands which support important industries will deteriorate. Nothing is to be gained from the woodchipping industry, which, as a Tasmanian once told me, is one of the most ruthless ever to move into Australia. (And that is saying something!)

I have nothing whatever to say against the Japanese decision to increase and improve its own already large forest area at the expense of other countries weak or foolish enough to sacrifice theirs. Or to export pollutive industries such as wood-pulp mills from an already highly polluted country. I do question, first, the use to which our exported wood-pulp is being put in wasteful over-packaging, and second, the refusal of Japanese interests to pay a price which will allow us to regenerate the areas already devastated in their projects. Above all, I question the arguments put forward by foresters here in their favour and the extension of present areas into new ones. The so-called degeneracy of our native forests can, I think, (and my inspection of Errinundra seems to confirm it) be put down squarely at the doors of Forestry Commissions and governments. It results from poor management, bad practice, and lack of planning of land use both overall and in particular interests. CSIRO’s latest report indicates that more than half our present pastoral and agricultural land is eroded to the point where major and highly expensive works should be undertaken to save our soils and large areas should be withdrawn from production altogether for such works; and that much o9f this deterioration can be put down to unwise clearing of forests. We can’t afford to lose any more of our protective trees. We have a responsibility to the world itself to keep our soils as productive as possible, both for food to be consumed here and for export. We have absolutely no responsibility to devote more of our very scarce forests to the bulldozer and the woodchip industry to be turned into expensive and unnecessary packaging and litter.

That is why I think it is time for Australians who have an interest in this country’s future to unite in defence of our remaining forests. If greedy and paralytic governments decide to sell out more – in the face of what even foresters admit to be drastic environmental deterioration in present project areas – we must get rid of those governments in favour of others which will act to protect and regenerate them wisely, and to protect our essential interests in soils, water and offshore fishing industries. If we do not speak now, and speak loudly and clearly, we betray our own future. The trees which protect us are in imminent danger – and their danger is our own danger.